Movement is Medicine

The Most Powerful Prescription You Can Write Yourself

If a pill existed that could extend your lifespan, strengthen your heart, boost mood, reduce anxiety, regulate blood sugar, balance hormones, improve sleep, build resilience to trauma, and lower your risk of dozens of chronic diseases — it would be the most prescribed drug in history.

That “pill” already exists. It’s movement.

Not just exercise, but any form of intentional, repeated motion — walking, lifting, stretching, dancing, swimming, cleaning, or playing with your dog. The human body is designed for daily for movement, and when we move, every system — cardiovascular, metabolic, neurological, and immune — optimizes. And it’s never TOO LATE to begin!

1. Longevity, Cardiovascular Health, and Disease Prevention

More than 750,000 participants across 174 cohort studies show that even small increases in physical activity dramatically reduce mortality risk. Meeting the World Health Organization’s minimum guideline — 150–300 minutes of moderate or 75–150 minutes of vigorous activity per week — is associated with:

31% lower all-cause mortality

29% lower cardiovascular mortality

15–20% lower incidence of certain cancers (especially breast, colorectal, and endometrial)

Physiologically, this happens because movement:

Increases stroke volume (the amount of blood your heart pumps per beat)

Improves endothelial function and nitric oxide availability, reducing arterial stiffness

Enhances mitochondrial density and oxidative metabolism

Reduces chronic low-grade inflammation (CRP, IL-6)

Even brief “movement snacks” — 1-minute stair climbs or 3×10-second sprints — have measurable effects on VO₂ max and cardiovascular fitness.

Bottom line: Heart health isn’t about marathons — it’s about consistency. Move more, sit less, and accumulate effort across the day.

Moderate physical activity refers to movement that noticeably increases your heart rate and breathing, but still allows you to hold a conversation (the “talk test”). It’s more intense than gentle walking but not so hard that you’re gasping for air.

Here’s how it’s defined scientifically:

Physiological definition

Heart rate: about 50–70% of your maximum heart rate

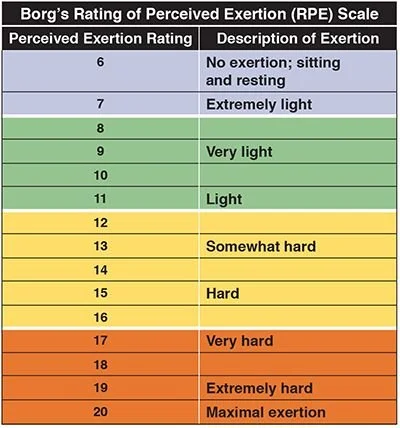

(Roughly: 220 minus your age = max HR; multiply by 0.5–0.7 for the target zone.)Perceived exertion: around 11–13 on the Borg RPE scale (6–20) — “somewhat hard.”

MET value (metabolic equivalent): typically 3.0–5.9 METs, meaning 3–6× the energy used at rest.

Common examples of moderate activity

Brisk walking (3–4 mph on level ground)

Leisure cycling (<10 mph)

Water aerobics

Hiking on gentle terrain

Gardening or yard work

House cleaning or carrying light loads

Recreational dancing or pickleball

Mowing the lawn with a push mower

Scientific benchmarks

According to the World Health Organization and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, adults should accumulate 150–300 minutes per week of moderate-intensity aerobic activity for optimal health benefits. You can mix and match with vigorous activity (where you can’t speak more than a few words without pausing) using this rough equivalence:

1 minute of vigorous activity ≈ 2 minutes of moderate activity

2. Metabolic Health, Blood Pressure, and Insulin Sensitivity

Exercise is one of the most potent known metabolic regulators.

Meta-analyses show that aerobic and resistance training lower systolic blood pressure by 4–9 mmHg, comparable to first-line medications.

For glucose regulation, ~150 minutes of mixed aerobic and resistance activity per week can reduce HbA1c by 0.5–0.7 percentage points in people with Type 2 Diabetes — rivaling drug therapy.

Increased GLUT-4 receptor expression, improving glucose uptake in skeletal muscle

Enhanced insulin receptor sensitivity

Elevated AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activity, mimicking metabolic fasting signals

Reduction in visceral fat, which drives insulin resistance

The takeaway: movement is the most powerful tool for metabolic flexibility — your ability to efficiently switch between burning fat and carbohydrates.

3. Mood, Stress, and Trauma Recovery

Exercise changes the brain on a structural level.

Within weeks, regular movement boosts levels of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), a growth protein that encourages neuroplasticity — the brain’s ability to form and reorganize neural connections.

Neurochemical and structural effects:

Increased dopamine and serotonin → improved motivation and mood

Elevated endorphins and endocannabinoids → pain modulation and calm

Growth of new neurons in the hippocampus, improving memory and emotional regulation

Reduced amygdala hyperactivation, decreasing reactivity to stress and trauma

Movement and trauma

Groundbreaking work by Dr. Bessel van der Kolk and others has shown that movement reconnects the body and mind after trauma.

In a 2014 randomized controlled trial, women with chronic PTSD who practiced trauma-sensitive yoga once a week for 10 weeks had significant reductions in hyperarousal and intrusive symptoms compared to controls.

Aerobic activity shows similar results. Exercise normalizes cortisol rhythms, enhances vagal tone, and strengthens prefrontal-amygdala communication — literally rewiring how the brain responds to stress.

Movement teaches the nervous system that the body is safe again — a cornerstone of trauma recovery.

4. Musculoskeletal Strength and Pain Resilience

Your musculoskeletal system thrives on load. Without regular resistance, bone density and muscle mass decline 1–2% per year after age 30. Strength training counteracts that loss — even 1 hour (easily divided into five 20 min sessions or two 30 min sessions) per week reduces all-cause mortality by 27%.

Mechanisms:

Mechanical loading stimulates osteoblasts, improving bone mineral density

Myokine release (IL-6 in its anti-inflammatory role, irisin) supports systemic metabolism

Improved proprioception reduces fall risk and joint instability

Cartilage perfusion improves with motion, reducing stiffness

In osteoarthritis, structured exercise (aerobic + resistance) consistently reduces pain and improves function.

“Motion is lotion” isn’t just a saying — it’s cellular truth.

5. Inflammation, Immunity, and Longevity Pathways

Moderate exercise acts as a systemic anti-inflammatory.

While high-intensity overtraining can transiently raise inflammatory cytokines, regular moderate activity reduces chronic inflammation markers by up to 30–40%.

Mechanistic highlights:

Down-regulation of TNF-α and IL-1β

Up-regulation of IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine

Mobilization of natural killer cells and macrophages

Enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis and autophagy, promoting cellular cleanup

Studies in older adults show that physically active individuals have longer telomeres — markers of cellular aging — suggesting that movement may literally keep your cells younger.

6. Sedentary Behavior: The Modern Health Hazard

Extended sitting independently predicts higher mortality, even in people who exercise.

Accelerometer data reveal that 30–40 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous activity per day can offset most of the mortality risk associated with 10 hours of sitting.

Swapping just one hour of sitting for light activity (walking, standing tasks) significantly reduces cardiovascular and metabolic risk.

The rule: Move every hour, not just at the gym.

7. The Ideal “Dose” of Movement

For General Health

150–300 minutes/week of moderate activity (RPE 12–14)

or 75–150 minutes/week of vigorous activity (RPE 15–17)

2+ strength sessions/week, targeting all major muscle groups

Break up sitting every 30–60 minutes with short movement bouts

For Enhanced Healthspan & Resilience

Add daily mobility or yoga

Include interval training (HIIT or sprint repeats 1–2× weekly)

Incorporate outdoor movement for sunlight exposure and circadian balance

Prioritize recovery: adequate sleep, hydration, and nutrition

8. The Real Medicine

Movement is not punishment for what you eat — it’s communication with your biology.

Every step, stretch, and lift sends a molecular message that says: “Grow, repair, adapt, and thrive.”

As The Wellness Lounge often reminds clients:

“Don’t compromise health for success — move toward both.”

Some of our favorite places to move:

References

World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour (2020).

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd ed.

García et al. Br J Sports Med (2023): Dose–response meta-analysis linking higher physical activity to lower all-cause mortality, CVD, and certain cancers.

Martinez-Gomez et al. JAMA Netw Open (2024): Physical activity and all-cause mortality across ages; HR ~0.78 for meeting guidelines.

Stamatakis et al. Nat Med (2022): Vigorous incidental lifestyle activity and mortality risk (VILPA).

Ahmadi et al. Lancet Public Health (2023): Sub-1-minute MVPA bouts associated with lower mortality.

Noetel et al. BMJ (2024): Exercise as treatment for depression—systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs.

Bizzozero-Peroni et al. JAMA Netw Open (2024): Daily steps and depression—systematic review/meta-analysis.

Edwards et al. Br J Sports Med (2023): Network meta-analysis—exercise training lowers resting blood pressure.

Gallardo-Gómez et al. Diabetes Care (2024): Optimal physical activity dose to improve HbA1c.

Xie et al. Frontiers in Psychiatry (2021): Exercise improves sleep quality/insomnia.

Ekelund et al. Br J Sports Med (2020): Sedentary time, MVPA, and mortality—accelerometer harmonized meta-analysis.

Shailendra et al. Am J Prev Med (2022): Resistance training and mortality—dose-response meta-analysis.

Lawford et al. (Cochrane, 2024 update): Exercise for knee osteoarthritis—pain and function benefits.

Iso-Markku et al. Br J Sports Med (2022): Physical activity and lower risk of all-cause, Alzheimer’s, and vascular dementia (meta-analysis).

Kruk et al. (2025 review): Physical activity and cancer incidence/mortality—strongest evidence for colorectal, breast, endometrial cancers.